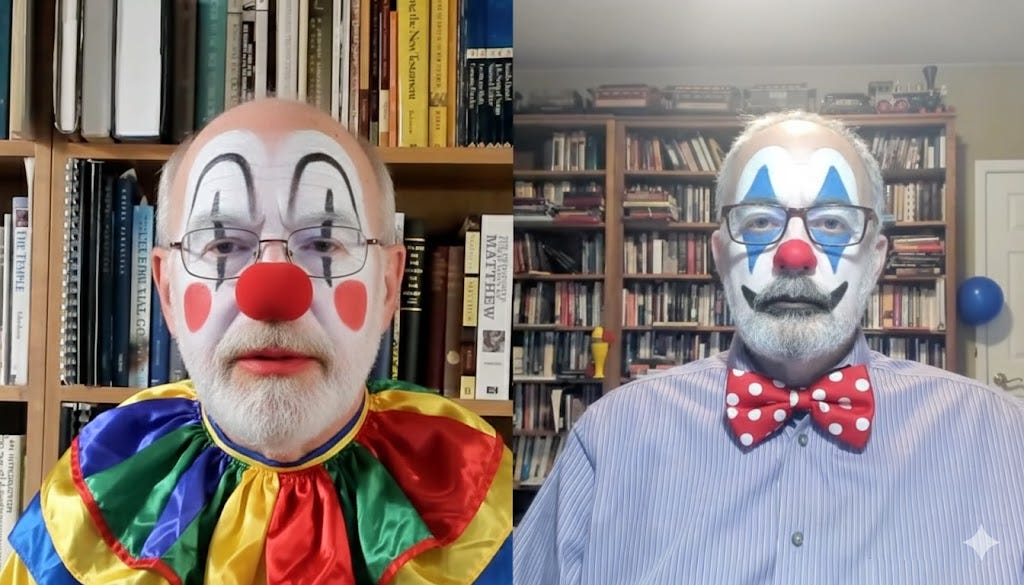

The Full Preterist Antics of Gary DeMar and Ed Stevens

Forty Years of Questions and Still No Resurrection

Gary DeMar and Ed Stevens recently sat down for an interview in which they revisited old preterist debates. The interview tries to reframe this whole controversy as if the only thing happening is that critics are overreacting to honest inquiry. It leans hard on the credibility of past conversations and past personalities, particularly the 1993 symposium, as if the existence of a meeting proves the legitimacy of the view. It does not. Reformed men discussing an error does not turn the error into an option. The church has always had to examine and refute errors. A panel and a cordial tone do not baptize a doctrine. The question is whether the teaching conforms to the apostolic gospel.

Gary’s tone throughout the interview is revealing. He repeatedly signals that the problem is that people cannot handle questions, that critics are uninformed, that discussion has been shut down, that the atmosphere has become unfair. This is the oldest rhetorical move in the book. Shift the discussion from content to posture. Suggest that the real sin is being too certain. Cast yourself as the brave questioner who is being bullied for curiosity. But the church does not label something heresy because a man is curious. It labels it heresy because a man denies a basic article of the faith. When someone denies the bodily resurrection, the issue is not that he asked a question. The issue is that he has rejected an answer Scripture gives plainly.

I am not speaking as someone guessing from the sidelines or reacting emotionally to a clip. I spent seven years active in the full preterist movement. I know these people. I know the arguments. I know the internal disputes. Gary even attempted to “debate” me, his word not mine, and then ran off. For the record, I currently serve as interim president of Whitefield Theological Seminary. I am not speculating from a distance. I am more familiar with this debate, historically and theologically, than Gary DeMar is. So when Gary tries to wave off critics as ignorant or uninformed, he is not describing reality. He is protecting a narrative.

The interview also showcases what has always been true about full preterism. It cannot even keep its own story straight on the resurrection. Ed Stevens rejects Max King’s collective body view, but then he offers his own alternative, which amounts to a resurrection of souls out of Hades and, in practical effect, an individual reception of the immortal body at death. He acknowledges critics have labeled his position that way. The point is not what nickname you give it. The point is what it does to the biblical doctrine. It turns the resurrection from the future transformation of embodied persons into either a covenantal metaphor or a postmortem shortcut that empties Paul’s argument of its force.

Ed also admits something that should not be ignored. At the 1993 symposium, the Reformed participants were uncomfortable with King’s resurrection approach. That is not a minor detail. That discomfort was not because they were mean, or because they could not handle questions, or because they were threatened by new ideas. It was because they recognized the theological stakes. Even in the interview, Ed recounts how Robert Strimple pressed the issue directly and warned that the gospel was at stake if you downplay the physical death and physical resurrection of Christ and shift significance into a spiritualized scheme. Ed says that critique became a turning point for him. Fine. But what did he do with that turning point? He did not return to the historic and biblical doctrine of bodily resurrection. He built a different model that still cannot carry the weight of 1 Corinthians 15!

This is where the interview tries to distract. It spends a lot of time on R.C. Sproul asking timing questions, especially about Matthew 24 and the language of nearness, and then it attempts to smuggle the resurrection debate in under that umbrella. The implied argument is that if Sproul can ask hard questions about Matthew 24, then Gary can ask hard questions about resurrection without being treated as heretical. But that is a sleight of hand. Sproul pressing the nearness language in the Olivet Discourse is not the same thing as redefining resurrection into something other than bodily resurrection. There is a difference between asking what is already and what is not yet and why, versus replacing the content of the resurrection hope with a different doctrine entirely.

The New Testament simply does not allow you to redefine resurrection into souls leaving Hades, or into a corporate covenantal transition, while evacuating bodily continuity. Start with 1 Corinthians 15, because Paul chooses this topic precisely to confront denial. He is not answering, “Where do souls go when they die?” He is confronting people who deny resurrection at all. His response is not, “Of course there is resurrection because souls go to heaven.” His response is, “Christ has been raised,” and Christ’s resurrection is the pattern and guarantee of ours. Paul’s argument depends on the bodily reality of Christ’s resurrection. If Christ’s resurrection is reduced to a spiritual transition, Paul’s logic collapses. He explicitly ties the gospel to a real resurrection such that if Christ has not been raised, preaching is empty, faith is futile, and we remain in our sins (1 Corinthians 15:14–17, ESV). Christianity stands or falls on the resurrection of Jesus, and the resurrection of Jesus is the public, embodied vindication of the crucified Christ.

The Gospels underscore this in the clearest terms. The risen Christ does not present himself as a mere spirit. He identifies his resurrected state as tangible and bodily: “See my hands and my feet, that it is I myself. Touch me, and see. For a spirit does not have flesh and bones as you see that I have” (Luke 24:39, ESV). He eats before them (Luke 24:42–43, ESV). The tomb is empty. The body is not there (Luke 24:3, ESV; John 20:6–7, ESV).

Then Paul turns from Christ to believers and explains resurrection with seed imagery, because it is the perfect way to hold together both continuity and transformation. What is sown is raised (1 Corinthians 15:36–44, ESV). It is transformed, glorified, and perfected. But it is not replaced by a different entity with no continuity. Paul even says, “This perishable body must put on the imperishable, and this mortal body must put on immortality” (1 Corinthians 15:53, ESV). Notice what happens. The perishable does not vanish into nonexistence. It puts on imperishability. The mortal puts on immortality. That is embodied persons being changed, not disembodied souls receiving a different body at death. Paul presses the same point when he says, “We shall not all sleep, but we shall all be changed” (1 Corinthians 15:51, ESV). The hope is not merely that souls escape Hades. The hope is the transformation of the whole man, body and soul, according to the pattern of Christ.

This also harmonizes with the broader New Testament witness. Jesus speaks of an hour coming when those in the tombs will hear his voice and come out (John 5:28–29, ESV). Paul in Athens ties the certainty of future judgment to the fact that God raised Jesus from the dead (Acts 17:31, ESV). Paul tells the Philippians that Christ “will transform our lowly body to be like his glorious body” (Philippians 3:21, ESV). He tells the Romans that we groan while waiting for “the redemption of our bodies” (Romans 8:23, ESV). That is the shape of Christian hope, and it is tied to Christ’s own bodily resurrection and to the consummation of his kingdom.

This is why the interview’s attempt to cast the dispute as a personality conflict, or as a dispute over whether people are allowed to ask questions, is so misleading. No orthodox Christian is threatened by earnest inquiry. What orthodox Christians reject is the redefinition of resurrection into something Scripture does not teach. And this is why Ed Stevens is full of baloney when he presents his view as if it solves the problem. It does not. Even within full preterism, many reject his approach because he cannot explain how the same body that is sown is the same body that is raised.

Ironically, Max King himself saw that difficulty. King recognized that Ed’s view could not account for the grammar and logic of 1 Corinthians 15, especially Paul’s insistence on identity and continuity between what is sown and what is raised. King’s solution, however, was not to return to the apostolic doctrine of bodily resurrection, but to redefine “body” itself as a metaphor. On King’s scheme, the “same body” is preserved only because the body is no longer a literal body at all, but a corporate, covenantal entity that undergoes transformation. That move does preserve grammatical continuity, but it does so at the cost of evacuating the passage of its actual meaning.

And Paul is not teaching that either. In 1 Corinthians 15, Paul does not redefine the body into a metaphor in order to save continuity. He explicitly contrasts kinds of bodies while maintaining personal, embodied identity. The seed analogy depends on real continuity, not on a shift from literal to figurative referents. What is sown is transformed, not replaced, and not reimagined as a different category altogether. King’s solution fails for the same reason Ed’s fails, just in the opposite direction.

You will not even get full preterists to agree on the resurrection. One side cannot explain bodily continuity, the other explains it away. That alone should tell you that the movement has not “hammered out” the doctrine, despite the confident tone with which they speak.

There is another layer of irony here. Gary tries to position himself as distancing from Max King, but Burgess and company are echoing Max’s basic move. They may change the packaging and adjust terminology, but the result is the same: the bodily resurrection of the dead is denied or displaced. That connection is not conjecture. I have documented it on this blog. Just search for “Max King.” So when Gary wants to be seen as a careful critic of extremes while he promotes authors who reproduce the same denial in a new dialect, the posture does not match the substance.

The church has always been willing to talk, to debate, to examine claims, and to test everything by the Word of God. That is not the issue. The issue is whether men will submit their systems to Scripture or twist Scripture to protect their systems. It is one thing to wrestle with the nearness language and the significance of A.D. 70. It is another thing to preserve your interpretive scheme by altering the content of the resurrection hope. When you do that, the question is not whether you are “asking questions.” The question is whether you are denying what the apostles preached.

So no, Gary was not criticized simply for “asking questions.” He was criticized because he denies the bodily resurrection, among a few other things. And both Gary and Ed have gotten answers. They just do not like them.

Heretics