What Is Critical Race Theory?

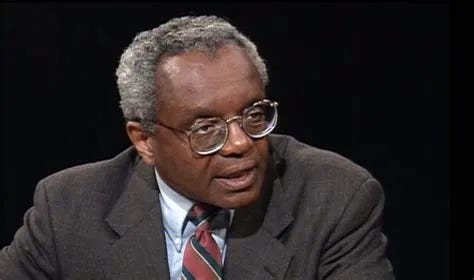

Answered by Derrick Bell

As to the what is, critical race theory is a body of legal scholarship, now about a decade old, a majority of whose members are both existentially people of color and ideologically committed to the struggle against racism, particularly as institutionalized in and by law. Those critical race theorists who are white are usually cognizant of and committed to the overthrow of their own racial privilege.

Critical race theory writing and lecturing is characterized by frequent use of the first person, storytelling, narrative, allegory, interdisciplinary treatment of law, and the unapologetic use of creativity.

The work is often disruptive because its commitment to anti-racism goes well beyond civil rights, integration, affirmative action, and other liberal measures. This is not to say that critical race theory adherents automatically or uniformly "trash" liberal ideology and method (as many adherents of critical legal studies do). Rather, they are highly suspicious of the liberal agenda, distrust its method, and want to retain what they see as a valuable strain of egalitarianism which may exist despite, and not because of, liberalism.

There is, as this description suggests, a good deal of tension in critical race theory scholarship, a tension that Angela Harris characterizes as between its commitment to radical critique of the law (which is normatively deconstructionist) and its commitment to radical emancipation by the law (which is normatively reconstructionist). Harris views this tension - between "modernist" and "postmodernist" narrative - as a source of strength because of critical race theorists' ability to use it in ways that are creative rather than paralyzing. Harris explains:

CRT is the heir to both CLS [Critical Legal Studies] and traditional civil rights scholarship. CRT inherits from CLS a commitment to being "critical," which in this sense means also to be "radical" [while] . . . [a]t the same time, CRT inherits from traditional civil rights scholarship a commitment to a vision of liberation from racism through right reason. Despite the difficulty of separating legal reasoning and institutions from their racist roots, CRT's ultimate vision is redemptive, not deconstructive.

Consider how the two groups view the law. Duke English Professor Stanley Fish explains the critical legal studies view of legal precedent as not a formal mechanism for determining outcomes in a neutral fashion - as traditional legal scholars maintain - but is rather a ramshackle ad hoc affair whose ill-fitting joints are soldered together by suspect rhetorical gestures, leaps of illogic, and special pleading tricked up as general rules, all in the service of a decidedly partisan agenda that wants to wrap itself in the mantle and majesty of law.

Adherents of critical race theory basically agree with this assessment. They depart from their critical legal theory colleagues regarding what is to be done with this tangle of illogic and corrupted jurisprudence. I think Professor Patricia Williams speaks for most practitioners of critical race theory when she concedes that the concept of rights is indeterminate, vague, and disutile. She readily acknowledges as example that the paper-promises of enforcement packages like the Civil Rights Act of 1964 have held out as many illusions as gains. Recognizing further that blacks have never fully believed in constitutional rights as literal mandate, Williams states (in terms that constitute as much creed as response):

To say that blacks never fully believed in rights is true; yet it is also true that blacks believed in them so much and so hard that we gave them life where there was none before. We held onto them, put the hope of them into our wombs, mothered them-not just the notion of them. We nurtured rights and gave rights life. And this was not the dry process of reification, from which life is drained and reality fades as the cement of concep- tual determinism hardens round-but its opposite. [This was the story of Phoenix]; the parthenogenesis of unfertilized hope.

It seems fair to say that most critical race theorists are committed to a program of scholarly resistance, and most hope scholarly resistance will lay the groundwork for wide-scale resistance. Veronica Gentilli puts it this way: "Critical race theorists seem grouped together not by virtue of their theoretical cohesiveness but rather because they are motivated by similar concerns and face similar theoretical (and practical) challenges.” To reiterate, the similar concerns referred to here include, most basically, an orientation around race that seeks to attack a legal system which disempowers people of color.

Although critical race theory is not cohesive, it is at least committed. As John Calmore observes, "almost all the critical race theory literature seems to embrace the ideology of antisubordination in some form."' It is our hope that scholarly resistance will lay the ground-work for wide-scale resistance. We believe that standards and institutions created by and fortifying white power ought to be resisted. Decontextualization, in our view, too often masks unregulated - even unrecognized - power. We insist, for example, that abstraction, put forth as "rational" or "objective" truth, smuggles the privileged choice of the privileged to depersonify their claims and then pass them off as the universal authority and the universal good. To counter such assumptions, we try to bring to legal scholarship an experientially grounded, oppositionally expressed, and transformatively aspirational concern with race and other socially constructed hierarchies. John Calmore puts it well:

[C]ritical race theory can be identified as such not because a random sample of people of color are voicing a position, but rather because certain people of color have deliberately chosen race-conscious orientations and objectives to resolve conflicts of interpretation in acting on the commitment to social justice and antisubordination.

Professor Charles Lawrence speaks for many critical race theory adherents when he disagrees with the notion that laws are or can be written from a neutral perspective. Lawrence asserts that such a neutral perspective does not, and cannot, exist - that we all speak from a particular point of view, from what he calls a "positioned perspective.” The problem is that not all positioned perspectives are equally valued, equally heard, or equally included. From the perspective of critical race theory, some positions have historically been oppressed, distorted, ignored, silenced, destroyed, appropriated, commodified, and marginalized - and all of this, not accidentally. Conversely, the law simultaneously and systematically privileges subjects who are white.

Critical race theorists strive for a specific, more egalitarian, state of affairs. We seek to empower and include traditionally excluded views and see all-inclusiveness as the ideal because of our belief in collective wisdom. For example, in a recent debate over "hate speech," both Chuck Lawrence and Mari Matsuda made the point that being committed to "free speech" may seem like a neutral principle, but it is not. Thus, proclaiming that "I am committed equally to allowing free speech for the KKK and 2LiveCrew" is a non-neutral value judgment, one that asserts that the freedom to say hateful things is more important than the freedom to be free from the victimization, stigma, and humiliation that hate speech entails.

We emphasize our marginality and try to turn it toward advantageous perspective building and concrete advocacy on behalf of those oppressed by race and other interlocking factors of gender, economic class, and sexual orientation. When I say we are marginalized, it is not because we are victim-mongers seeking sympathy in return for a sacrifice of pride. Rather, we see such identification as one of the only hopes of transformative resistance strategy. However, we remain members of the whole set, as opposed to the large (and growing) number of blacks whose poverty and lack of opportunity have rendered them totally silent. We want to use our perspective as a means of outreach to those similarly situated but who are so caught up in the property perspectives of whiteness that they cannot recognize their subordination.

I am not sure who coined the phrase "critical race theory" to describe this form of writing, and I have received more credit than I deserve for the movement's origins. I rather think that this writing is the response to a need for expressing views that cannot be communicated effectively through existing techniques. In my case, I prefer using stories as a means of communicating views to those who hold very different views on the emotionally charged subject of race. People enjoy stories and will often suspend their beliefs, listen to the story, and then compare their views, not with mine, but with those expressed in the story.