The Illusion of Logic Behind Michael Sullivan’s Opening Argument

The Olivet Discourse Showdown: Breaking Down the Arguments

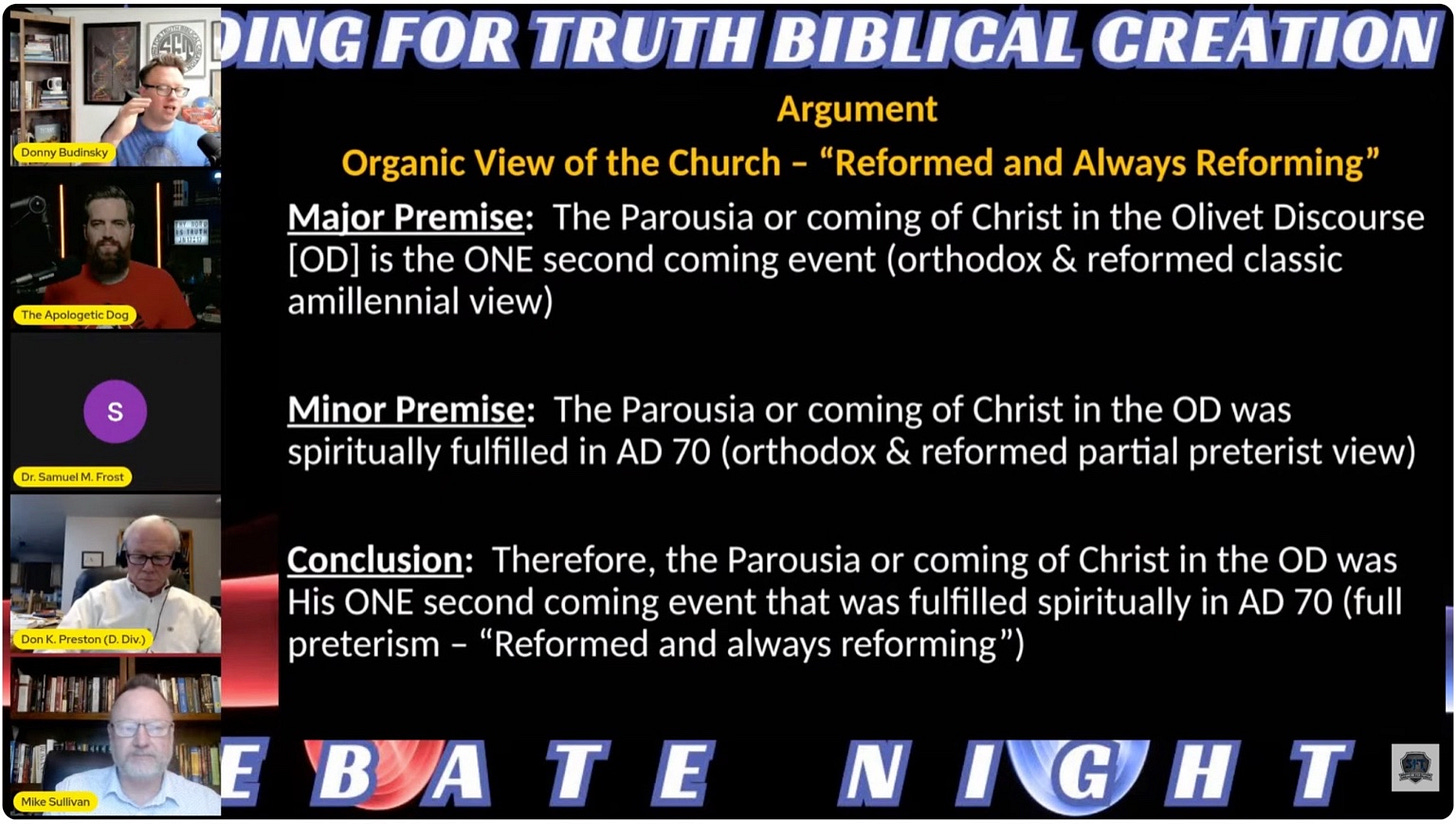

The graphic under discussion comes from a recent public debate between Don Preston and Michael Sullivan on one side and Sam Frost and Jeremiah Nortier on the other. The stated resolution of the debate was this: The Olivet Discourse predicted the destruction of Jerusalem in AD 70 and the end of the current age, the age that began with Adam and will continue until the end of human history. Sam Frost and Jeremiah Nortier argued the affirmative. Don Preston and Mike Sullivan argued the negative.

Each participant was given a twenty four minute opening statement. Michael Sullivan went first for Team Heresy (hyper-preterism), and the slide captured in the image was his very first argument. That choice is not surprising. Sullivan is well known for relying heavily on charts, diagrams, and what he presents as tightly constructed “syllogisms.” The visual format is meant to convey logical inevitability. Accept the premises, and the conclusion supposedly follows. But logical form only has force when the argument actually follows the rules of deduction. This one does not.

At first glance, the argument appears to be a clean deductive syllogism. It has a major premise, a minor premise, and a conclusion that claims to follow necessarily from the two. Because of that structure, many readers assume that if they accept the premises, they must also accept the conclusion. That assumption is only valid if the reasoning preserves meaning from beginning to end. In this case, it does not.

A deductive argument is valid only when the conclusion follows necessarily from the premises. Validity is not about whether the premises are true but about whether the logic holds. In a categorical syllogism, that logic depends on consistent use of terms. If a key term changes meaning between premises, the argument commits the fallacy of equivocation and the conclusion no longer follows.

A standard syllogism contains three terms. The major term appears in the major premise and the conclusion. The minor term appears in the minor premise and the conclusion. The middle term links the two premises but does not appear in the conclusion. For the argument to be valid, each term must be used in the same sense throughout. If the meaning of a term shifts, the logical connection collapses even if the wording remains identical.

In Sullivan’s argument, the controlling term is Parousia, or the coming of Christ. In the major premise, this term refers to the one second coming of Christ. It is treated as a singular and comprehensive eschatological event, namely the visible, bodily return of Christ to earth at the end of history. In the minor premise, the same word Parousia is used, but it is redefined as a “spiritual” event, a category misuse from the outset, namely a non bodily and non visible occurrence asserted to have been fulfilled in AD 70. The argument assumes that because the same word is used, the same referent is intended. That assumption is the precise point of failure.

This is a textbook example of equivocation. The fallacy of equivocation occurs when a term is used in one sense in the first premise and in a different sense in the second premise, while the conclusion treats the term as if it had remained unchanged. The language appears stable, but the meaning is not. Once meaning shifts, deduction is impossible.

A simple illustration makes this clear. Suppose someone argues that a “president” is the head of a nation, that a “president” can also be the head of a local club, and therefore the president of a chess club has authority over national policy. The term is identical, but the scope and nature of authority are not.

The same error occurs here. In the major premise, Parousia functions as a technical term referring to the final and bodily return of Christ. In the minor premise, Parousia is reframed as a so called spiritual, non bodily coming claimed to have been fulfilled in history. These are not identical in meaning or scope. The argument only works if the shift is ignored.

Because the term changes sense, the conclusion does not follow from the premises. Even if one were to grant both premises as stated, the conclusion would still be invalid. The argument fails before any theological evaluation is necessary. It fails on purely logical grounds.

What gives this argument its rhetorical force is its presentation. Charts and syllogisms give the impression of rigor. But logical validity is not about visual clarity or confident delivery. It is about whether the conclusion is contained within the premises without any shift in meaning. Once the key term is equivocated, the chain of reasoning snaps.

Consistency of terms is not a technicality. It is the foundation of all deductive reasoning. When an argument equivocates, it does not lead the reader to a conclusion. It nudges the reader there by quietly changing definitions midstream. That is not logic. It is verbal manipulation.

This is why Sullivan’s opening argument fails so quickly. It is not refuted by downstream theological implications or confessional commitments. It is refuted by Logic 101. A conclusion drawn from shifting terms is not a conclusion at all. It is a non sequitur dressed up as precision.

This post has intentionally focused on only the opening argument and only on its logical structure. There were many other claims made throughout the debate that deserve careful examination, and I may return to those in future posts. For now, it is sufficient to note that when the very first argument offered fails at the level of basic deduction, the burden of proof does not shift to the listener. It remains squarely on those who insist that invalid syllogisms can substitute for clear thinking.