The Illusion of Logic Even Without Equivocation

The Olivet Discourse Showdown: Breaking Down the Arguments

In my previous post, I focused on the most obvious logical failure in Michael Sullivan’s opening argument, namely equivocation. The argument collapses because the same term is used with different meanings across the premises. That alone is sufficient to render the conclusion invalid. In this follow up, I want to slow the argument down even further and show that the problem runs deeper. Even if we momentarily ignore equivocation, the argument still does not conform to any valid categorical syllogistic form.

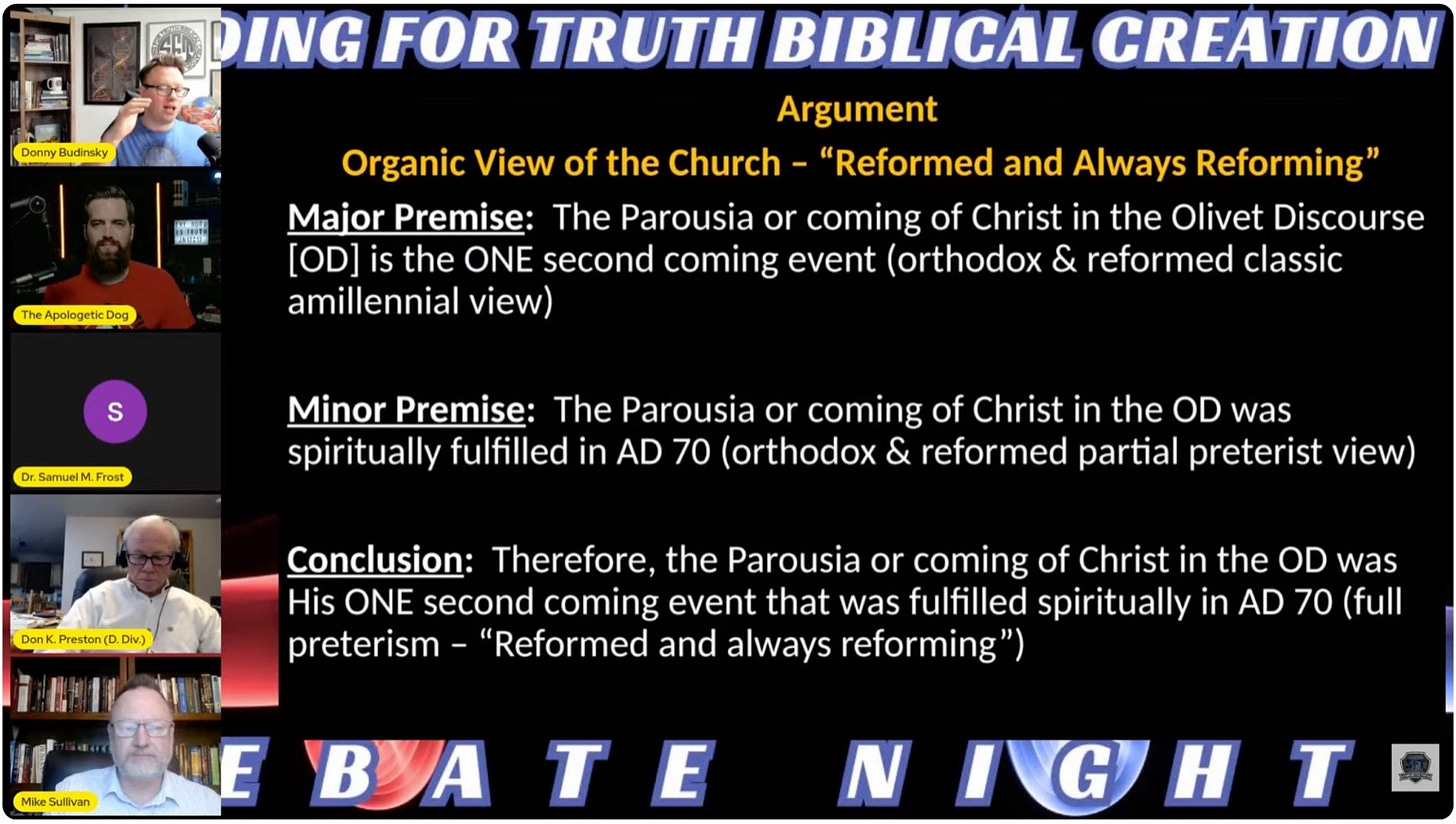

Sullivan presents his argument visually as if it were a straightforward deductive syllogism. The implied claim is that the conclusion follows necessarily from the premises. When an argument is presented this way, it is fair to ask a basic question. What kind of syllogism is this supposed to be?

Classical logic does not treat every three line argument as valid simply because it has two premises and a conclusion. Categorical syllogisms are governed by strict rules and recognized forms. These forms are classified by figure, which is determined by the position of the middle term, and by mood, which refers to the type of propositions used in the premises and the conclusion. Only certain combinations of mood and figure are valid. Anything outside those combinations fails as deduction.

Before listing the valid forms, it is helpful to clarify what is meant by mood. In categorical logic, each premise and the conclusion falls into one of four types, traditionally designated by the letters A, E, I, and O.

A propositions are universal affirmatives. They assert inclusion without exception, as in “All A are B.”

E propositions are universal negatives. They deny inclusion entirely, as in “No A are B.”

I propositions are particular affirmatives. They assert that at least some members of a class are included, as in “Some A are B.”

O propositions are particular negatives. They assert partial exclusion, as in “Some A are not B.”

The mood of a syllogism is simply the sequence of these proposition types in the major premise, minor premise, and conclusion. For example, a syllogism labeled AAA uses three universal affirmatives. A syllogism labeled EIO uses a universal negative, followed by a particular affirmative, and ends with a particular negative.

Traditionally, there are four figures of categorical syllogisms. Within those figures, only a limited number of moods are valid.

In the first figure, where the middle term is the subject of the major premise and the predicate of the minor premise, the valid moods are Barbara (AAA), Celarent (EAE), Darii (AII), and Ferio (EIO). Barbara (AAA) is the most familiar. Its structure is simple and intuitive. All M are P. All S are M. Therefore, all S are P. When the terms are used consistently, the conclusion follows necessarily.

In the second figure, where the middle term is the predicate of both premises, the valid moods are Cesare (EAE), Camestres (AEE), Festino (EIO), and Baroco (AOO). These forms typically establish exclusion rather than direct inclusion.

In the third figure, where the middle term is the subject of both premises, the valid moods are Darapti (AAI), Disamis (IAI), Datisi (AII), Felapton (EAO), Bocardo (OAO), and Ferison (EIO). These syllogisms usually yield particular conclusions rather than universal ones.

In the fourth figure, which is less intuitive and was recognized later in the tradition, the valid moods are Bramantip (AAI), Camenes (AEE), Dimaris (IAI), Fesapo (EAO), and Fresison (EIO).

That list represents the entire classical set. If an argument does not fit one of these moods in one of these figures, it is not a valid categorical syllogism.

The form Sullivan appears to be aiming for is the most basic and familiar of all, Barbara (AAA) in the first figure. This is the form most people instinctively think of when they hear the word syllogism. It carries a sense of inevitability. Grant the premises, and the conclusion must follow.

Sullivan’s argument is clearly trying to trade on that sense of inevitability. But when the premises are actually laid out, the structure does not match Barbara (AAA) at all.

If we translate the argument into categorical terms, it looks like this. Let P stand for the one second coming of Christ. Let M stand for Parousia. Let S stand for an event fulfilled spiritually in AD 70.

The major premise is presented as: all M are P. All Parousia refer to the one second coming of Christ.

The minor premise is then presented as: all M are S. The Parousia was fulfilled spiritually in AD 70.

And the conclusion drawn is effectively: therefore, all P are S. The one second coming of Christ was fulfilled spiritually in AD 70.

Even before we address equivocation, this is not a valid AAA syllogism. In Barbara (AAA), the minor premise must be all S are M, not all M are S. Sullivan reverses the relationship. As a result, the conclusion attempts to make a universal claim about P without P ever being properly distributed in the premises. That is a formal error.

Nor does the argument reduce to any other valid mood in any figure. It is not a second figure syllogism such as Cesare (EAE) or Camestres (AEE), since the middle term is not consistently predicated. It is not a third figure syllogism such as Darapti (AAI) or Datisi (AII), since the conclusion is universal rather than particular. It is not a fourth figure syllogism such as Bramantip (AAI) or Camenes (AEE), since the required distributions are not satisfied. The argument simply does not instantiate any recognized valid form.

In other words, even if the term Parousia meant the same thing everywhere, the argument still would not follow. The structure itself is flawed. It looks like a syllogism, but it is not one.

Once we reintroduce the definitional shift, the problem becomes even more severe. In the major premise, Parousia refers to the final, visible, bodily return of Christ. In the minor premise, Parousia is redefined as a so called “spiritual” and non bodily event fulfilled in AD 70. That means the middle term is no longer a single term at all. It has split into two. At that point, the argument contains four terms instead of three, which is fatal to any categorical syllogism.

This is why the argument only works when presented quickly and visually. Charts can mask structural problems. Labels can create the illusion of rigor. But once the argument is translated into standard logical form and the terms are held still long enough to be examined, the deduction evaporates.

The takeaway is simple. Sullivan’s opening argument does not merely fail because of equivocation, though it certainly does that. It also fails because it does not instantiate any valid syllogistic mood or figure. The conclusion is not forced by the premises. It is asserted and then dressed up to look necessary.

This is why spending time on logic matters. When someone claims that their conclusion follows inevitably from their premises, the burden is on them to show that it actually does. In this case, it does not.

As before, this post has focused on a single argument and a single issue. There were many other claims made in the debate that could be examined with the same care. I may return to those in future posts. For now, it is enough to say this. When an argument fails both formally and materially, no amount of emotion and repetition cannot rescue it.