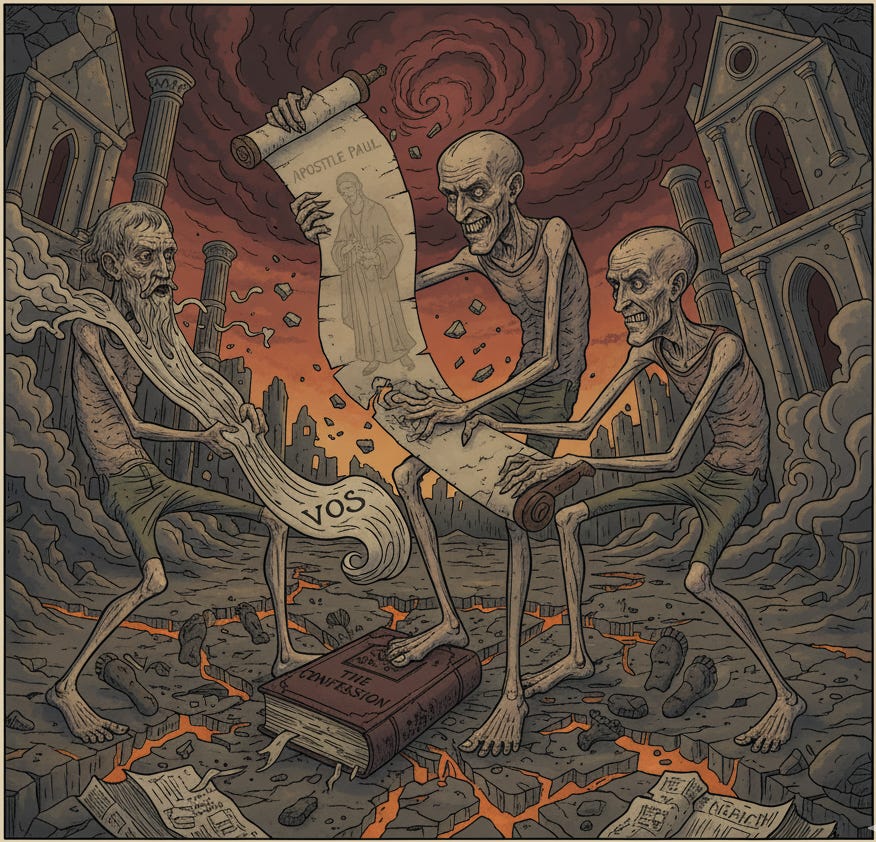

Twisting the Apostle Paul, Warping Vos, and Trampling the Confession: Gary DeMar and Kim Burgess's Assault on the Resurrection

In their second episode on 1 Corinthians 15, hyper-preterists Gary DeMar and Kim Burgess double down on their distortion of Paul’s teaching, peddling a resurrection that bears little resemblance to anything found in Scripture or the historic Christian faith. They argue that the historic Christian understanding, as reflected in creeds like the Westminster Confession, has been wrong about the resurrection of the body. According to their heresy, Paul’s focus is on the resurrection of the dead (persons), not a resurrection of the physical body, and the “spiritual body” believers receive is something altogether different from our present bodies. They even enlist theologian Geerhardus Vos to support the idea of a radical discontinuity between the body that dies and the body that rises. According to Burgess, the confessional phrase “the self-same body” coming out of the grave is a mistake. He claims “my body that I have going into [death] and coming out are two different bodies”. In short, they assert that flesh-and-bone continuity is out, and a new “spiritual” embodiment is in.

As we will see, DeMar and Burgess’s interpretation doesn’t simply misread Paul; it mutilates him. Their handling of 1 Corinthians 15 turns one of the most glorious affirmations of bodily resurrection in all of Scripture into a hollow exercise in wordplay. Their misuse of Vos is worse still, yanking his precise exegetical distinctions into service of a theology he himself would have repudiated. Far from recovering the true Pauline hope, their project drags old heresies out of the grave.

The Reformed confessional witness, by contrast, remains unshaken: God will raise our “self-same bodies, and none other, although with different qualities.” That doctrine is not naïve, ignorant “futurism;” it is the heart of biblical Christianity, grounded in the resurrection of Christ Himself, the firstfruits and pattern of all who belong to Him.

The Podcast’s Claims: A Radical Discontinuity in the Resurrection Body

Burgess and DeMar open by insisting that 1 Corinthians 15 is about the “resurrection of the dead,” not specifically the resurrection of the body. The distinction is key for them: they see “the dead” as persons who will indeed be raised, but they regard the body as a “subordinate question” (in Burgess’s words) – merely what kind of body the raised persons will have. This might sound harmless, but they draw a startling conclusion: the body that is raised is not the same body that died. Using Paul’s seed analogy, Burgess argues that the corpse which is “sown” perishes completely like a seed, and God then creates a new body for the person who is raised. In his own analogy, the human body is like a kernel of corn that dies and “is gone forever” so that a new plant can emerge. The only continuity, he says, is the “essence” or identity – “It’s me that’s raised” – but “my body…going in and coming out are two different bodies”.

This leads Burgess to flatly declare that the Westminster divines and historic creeds “got it wrong.” In the podcast he ridicules the confessional language: “Absolutely, they got it wrong. They just like the body A goes in the ground and body B comes back out of the ground, just refurbished a little bit. No, that’s not the way it works”. He specifically targets the phrase “self-same body,” calling it “the mistake…where they went off the rails.” “It’s not the self-same body any more than the corn stalk is the self-same body as the kernel,” Burgess insists. “Paul couldn’t have said it any clearer. And they still missed it.” They claim that the Church has misunderstood Paul for two thousand years, taking 1 Corinthians 15 as a straightforward affirmation of bodily resurrection instead of recognizing, as they imagine, a complete exchange of bodies.

Finally, DeMar and Burgess argue that the “spiritual body” (Greek σῶμα πνευματικόν, sōma pneumatikon) of which Paul speaks is not physical at all. It belongs to an entirely different order of existence – “a different kind of physics, if it’s anything than we’re used to,” says Burgess. Appealing to 1 Corinthians 15:47–49, they note that the first man (Adam) was formed from earth’s dust, but the second man (Christ) is “from heaven.” Paul pointedly doesn’t say what the heavenly body is “made of,” and for Burgess this omission is deliberate. “He’s saying it’s heavenly, and we want to say, ‘Made of what?’ and he doesn’t provide anything. There’s no alternative to the made of dust. It’s not a physical body. It’s a heavenly body. It’s a spiritual body, i.e., like the body that Christ has now,” Burgess argues. According to this view, Jesus’s resurrected/glorified body is non-material (or at least not “flesh and blood” in any ordinary sense), and so will ours be. They bolster this claim by citing Geerhardus Vos, a popular Reformed theologian, particularly his observation that Paul uses two different Greek words for “another” in verses 39–41. Paul says “all flesh is not the same flesh, but there is one kind (allos) of flesh of men, another of animals…” and “there are heavenly bodies and earthly bodies, but the glory of the heavenly is of one kind and the glory of the earthly is of another (heteros).” Vos noted that ἄλλος (allos) often means another of the same kind (specific difference within a genus) while ἕτερος (heteros) implies another of a fundamentally different kind. From this, Burgess concludes that the earthly body vs. heavenly body are “heterogeneous,” belonging to two different genus or orders of being. In his words, “that’s where the creedal confessions went wrong. They just assumed it’s… the same genus… Vos says no.” Even Vos, he claims, tacitly provided “ammunition” against the traditional view, by showing Paul’s intent of a radically different resurrection somatic mode.

Ignoring Their Own Problem: Disembodied Saints in Their System

These are not merely bold assertions, they are self-defeating ones. If true, they would mean that nearly the entire Church, from the apostles and fathers to the Reformers and beyond, has been wrong about the resurrection. But in reality, it is DeMar and Burgess who have twisted Paul’s message beyond recognition. I have pointed out before that their system creates the very problem they accuse the orthodox view of having, and to this day, that critique has gone unanswered.

They mock the historic Christian position for teaching that believers are with Christ in heaven in a disembodied state until the final resurrection, calling it unnatural and philosophically incoherent. As DeMar puts it:

So the traditional way is that you die, your spirit goes to heaven, but there is no body. You don’t get your body till the end sometime in the future. That seems to be unnatural in terms of what makes us who we are is to separate one from the other.

Yet the irony is glaring. Their own view leaves Old Testament believers disembodied for centuries. If resurrection bodies weren’t not made available until AD 70, then Abraham, Moses, and David spent millennia without their bodies before that event. Their lament about “bodiless saints” therefore collapses on their own premises. Their complaint is not solved; it is simply relocated.

The Reformed and apostolic view, on the other hand, is both consistent and biblical. It affirms that the intermediate state is temporary but blessed, awaiting the resurrection of the same bodies that were sown in death. This is not a “problem” for orthodoxy but a testimony to the already-not-yet tension of redemptive history. As Paul writes, we “groan inwardly as we wait eagerly for adoption as sons, the redemption of our bodies.” (Rom. 8:23). The saints presently in heaven await not a replacement but the glorification of the very bodies they once inhabited; a truth that honors both the continuity of creation and the victory of Christ’s bodily resurrection.

Firstfruits and “Foolish” Questions: What Paul Emphasized in 1 Corinthians 15

Before diving into Greek terms and analogies, we must begin where Paul begins. The first thirty-four verses of 1 Corinthians 15 establish the very foundation of the resurrection hope: Christ’s own bodily rising from the dead. The problem in Corinth was not curiosity about the nature of the resurrection body but unbelief in the fact of resurrection itself. Some were saying, “there is no resurrection of the dead” (1 Cor. 15:12). Influenced by Greek disdain for the material and skeptical of the body’s future, these critics considered the idea of corpses being raised both foolish and repulsive. Paul’s purpose, therefore, is to prove the certainty and necessity of bodily resurrection, and he does so by rooting it in the historical, physical resurrection of Jesus Christ.

If there is no resurrection of the dead, then not even Christ has been raised… But in fact Christ has been raised from the dead, the firstfruits of those who have fallen asleep (1 Cor. 15:13, 20).

Here Paul makes his argument unbreakable: the resurrection of believers is of the same kind as Christ’s. His empty tomb and bodily appearances (vv. 3–8) are not peripheral details; they are the theological anchor of the chapter. The term firstfruits means that Christ’s risen body is the prototype and guarantee of our own resurrection. Just as the first sheaf of the harvest shares the same nature as the rest of the crop, so our glorified bodies will share in the same kind of resurrection life as His.

DeMar and Burgess, however, all but skip this half of the chapter. They leap past verses 1–34 and start their discussion at verse 35, where Paul takes up the nature of the resurrection body. By doing so, they sever Paul’s argument from its essential foundation. They isolate the question “With what kind of body do they come?” (v. 35) from Paul’s preceding insistence that our resurrection must mirror Christ’s. The result is a theology of replacement, not resurrection. Their reading ignores the sequence of Paul’s thought: the firstfruits (Christ) determines the harvest (believers).

The linchpin of Paul’s reasoning is that the mode of our resurrection cannot differ from Christ’s; His bodily triumph is the prototype and pattern of our own. That is precisely why he emphasizes the empty tomb and physical appearances at the outset. Paul will not allow us to separate the resurrection’s mode from its meaning. To deny the bodily continuity between Christ’s resurrection and ours is to dismantle Paul’s logic entirely.

The gospel Paul preaches is triumphantly physical. It is not “fleshly” in the corrupt sense, but it most certainly involves the flesh—the same body that dies, raised and transformed by divine power. Any view that denies this continuity, whether ancient Corinthian or modern hyper-preterist, is not am informed reading of Paul’s theology but a rejection of it.

“How Are the Dead Raised?” – Paul’s Seed Illustration in Context

Burgess correctly notes that 1 Corinthians 15:35 raises two related questions: “How are the dead raised? With what kind of body do they come?” Paul’s response to the hypothetical skeptic begins sharply: “You fool!” – because the question betrays a doubting of God’s power and imagination. “What you sow does not come to life unless it dies,” Paul says, and “what you sow is not the body that is to be, but a bare kernel… But God gives it a body as He has chosen” (15:36–38). This is a brilliant analogy from agriculture. It’s designed to counter the scoffers’ assumption that resurrection is impossible or absurd by showing that transformation from one form to another is built into creation. From a dry seed, buried in the ground, God brings forth a green shoot and eventually a flourishing plant, something continuous with the seed (it is the same organism developing) yet gloriously different in form and beauty. As Geerhardus Vos observes:

No observation of a seed-grain could have taught, without previous experience, what the appearance of the sprout or plant issuing would be like. What right then has a man to argue from the impossibility of pre-vision and pre-imagination, to the presumptuous conclusion that the forthcoming of a new differently-shaped and differently-appareled body is a priori an absurdity?1

Paul’s rebuke aims at the skeptic’s lack of imagination and faith: just because we cannot visualize the exact nature of the resurrection body in its glory does not mean God cannot bring it about.

Importantly, Paul’s seed analogy does not suggest a total annihilation of the old with zero continuity into the new – quite the opposite. The core point is that the same seed that “dies” is what comes to life as a new plant. “What you sow” (the seed) “is what is quickened” (made alive) after the seed “dies.” As Vos highlights, “he affirms that that which is sown is quickened, and precisely what is sown dies. The subject is the same in both propositions.”2 In other words, the very same kernel that decays in the soil is raised up by God in a new, glorious form. There is continuity of identity, even though there is dramatic difference in appearance and qualities. If Paul meant to say, “The seed dies and disappears, and then God creates an entirely unrelated plant ex nihilo,” the analogy would fall apart – and the skeptic’s question would still stand (“How can this corpse come back?”). But Paul’s illustration implies that the corpse that “dies” is precisely what will be reanimated, though wondrously transfigured by God’s creative power. The “death” of the seed is real – it undergoes dissolution – but out of that very death God brings new life. Continuity and discontinuity coincide: the seed is transformed, not replaced by an entirely alien thing.

Burgess, however, leans heavily on the phrase “you do not sow the body that shall be” (v.37) to claim “that seed… it’s done its job… it’s gone forever”. But Paul’s phrase can be misunderstood here. He isn’t denying that the same seed becomes the plant; he’s simply stating the obvious fact that what you stick in the ground (a seed) is not in the final form of what comes out (a full plant). “The body that shall be” – the final flowering – is not yet visible at sowing. In farming terms, one could say we don’t bury an apple tree, we bury an apple seed. Yet apple seeds produce apple trees; they are one organism through developmental stages. Likewise, Paul’s point is that the resurrection life will be far more glorious than our present embodiment, just as a blooming plant is far more glorious than the naked seed. The emphasis is on God’s creative transformation, not on a swap or exchange of one thing for another. In fact, Paul explicitly says “what you sow does not come to life unless it dies” (v.36) – implying that the very thing that died is what comes to life. He does not say “unless it is replaced.” And interestingly, in commenting on the corruption of the body and death, DeMar and Burgess completely ignore the most concrete reality underlying Paul’s argument—the fact that Christ Himself truly died!

As A. Andrew Das observes:

In vv. 42–44 a σῶμα ψυχικόν is changed into a σῶμα πνευματικόν. The same subject governs vv. 42–44; it is the same body. Body x does not metamorphosize to body y, but a perishable body x is changed to an imperishable body x in what is not a subtraction but an addition, an enhancement.3

The seed gains new qualities (foliage, fruit) it never had, but it remains itself now perfected as God intends. In the resurrection, God “gives it a body as He pleases” (v.38) – just as He “clothes” the growing seedling with stalk, leaves, and grain – yet “to each kind of seed its own body.” The wheat seed does not turn into a barley plant, and a human person is not raised as an angel or some other creature; each receives its own appropriate body, preserving their identity in the new creation.

Vos drives this home in his commentary. He notes that in 1 Corinthians 15:39–41 Paul shifts to examples of diverse kinds of bodies in the present creation (human flesh, animal flesh, celestial bodies like sun and stars). Why? To underscore God’s prerogative and power to furnish appropriate bodies for different realms of life. There is “one glory of the sun, another of the moon…” – each thing has a somatic form suited to its environment and purpose, by God’s design. Thus, the skeptic has no ground to say a “differently constituted” resurrection body is inconceivable. Crucially, Vos highlights Paul’s careful language: alternating allos and heteros to distinguish variations within the same category versus differences between categories. In verse 39, all the creatures named (men, birds, fish, etc.) share the same broad “fleshly” genus (mortal, earth-bound life), so Paul uses allos (“another [of the same kind]”). In verse 40, by contrast, heavenly vs. earthly belongs to two different spheres, so he uses hetera (“different [in kind] glory”). Burgess seizes on this to say “earthly body” and “heavenly [resurrection] body” are as different as two separate genera, with no overlap. But Vos’s own conclusion is not what Burgess makes it out to be. Vos says, “the resurrection-body will differ greatly from the kind of body we now possess in its eradiation of glory. It will be a case of heteros and not merely of allos.”4 In other words, yes – the resurrection body belongs to a new order of existence (immortal, glorious, Spirit-filled) as opposed to our frail, corruptible natural state. Paul “likewise calls attention to the generic, fundamental difference between the realms”5 of the resurrection state and our current state. But difference in kind of existence is not the same as difference in identity or substance. Vos is talking about qualitative difference – what he calls a difference in “glory” or appearance (Gk. doxa) – not asserting that the old body is discarded. In fact, Vos explicitly warns against that misunderstanding:

The question is in order, whether in this context, so full of mysteries, there is actually present, as the evolutionary pneumatology would have it, such a powerful influx of the pneuma-principle as would overbear everything else, and even exclude the factor of the erstwhile earthly body from the process described. The answer must be in the negative.6

Vos goes on to observe that Paul avoids using the word “flesh” (sarx) for the resurrected body of believers precisely because in Paul’s usage sarx in such contexts carries connotations of sin and weakness. When describing the resurrection state, Paul switches to positive terms – incorruptible, glory, power, spiritual – to show that the old corruptibility and shame will be forever gone. “Flesh and blood,” in Paul’s idiom, denotes the frail, mortal nature we inherit from Adam, subject to decay. Thus “flesh and blood cannot inherit the kingdom of God” (v.50) is immediately explained by Paul to mean “nor does the perishable inherit the imperishable.” As Ware points out, Paul uses a little chiastic pattern here: “flesh and blood” is parallel to “the perishable,” and “inherit the kingdom” parallels “inherit the imperishable”.7 In short, “flesh and blood” is not a technical phrase for “physicality” per se, but a shorthand for our current perishable, corruptible mode of bodily life. And that mode truly cannot inherit God’s eternal kingdom. We must be changed. Our mortal bodies must “put on” immortality (v.53). But note: “putting on immortality” implies the same subject (our body/person) is clothed with new qualities, not that our body is left in the grave while something entirely different replaces it. Paul says “this perishable body must put on imperishability, and this mortal body must put on immortality” (15:53–54). He could not say it more plainly. This very body, which now can die, will put on deathlessness. There is no third thing substituted; it is creation renewed, not creation discarded.

So, when Burgess exclaims that Paul “never tells us what [the resurrection body] is made out of… We’ve crossed into a different realm of reality we have no idea about”, he is partly right – the resurrection life is a reality we have not yet experienced and cannot fully describe. “Eye has not seen, nor ear heard…” (1 Cor 2:9). But he is wrong to conclude that therefore our present bodies play no role in it. Paul “skirts” the carnal speculations about how God reconstitutes the body (e.g. what if it’s dust or dissolved?). Paul doesn’t give a scientific formula for reassembly of remains; rather, he redirects to the doctrine of transformation: God will change us. The mystery of how God will do it remains, but the fact that He will do it is certain. As Vos wisely concludes after examining various hypotheses: “Whichever way one turns, [trying to ‘explain’ the mechanics] proves impossible and futile. It is better to leave the matter where it is and to commit the working out of the mystery to God, who can bring about things unsearchable to the mind of man.”8 In other words, Scripture guarantees continuity (it is truly we who will be raised, in glorified somatic life), and it guarantees discontinuity (all the effects of sin and mortality will be forever removed). The precise “physics” of it God has not described, but He has given us sufficient conceptual handles: Christ’s risen body as our pattern, and the seed-to-plant analogy as our paradigm. The same Jesus who died is now alive, transformed, and so it will be for us.

The “Spiritual Body”: Pneumatiko vs. Psychiko

Much confusion in these debates revolves around Paul’s term “spiritual body.” In English that phrase can sound like an oxymoron, as if “body” were material and “spiritual” meant immaterial. But the Greek adjective pneumatikon in context does not mean “made of spirit” (as if our resurrection body will be a ghost or vapor). Rather, it describes a body determined by, filled with, and empowered by the Spirit. To grasp this, we must see Paul’s deliberate contrast: sōma psychikon vs. sōma pneumatikon, often translated “natural body” vs “spiritual body” (15:44). The first term, psychikos, comes from psuchē (soul, or the principle of life in the natural human). The second comes from pneuma (spirit, specifically here the Holy Spirit). As Burgess himself points out, psychikos could be literally rendered “soulish” – the sōma psychikon is the body suited to the psuchē-life we received from Adam. It’s the ordinary, soul-powered human body (“living soul,” v.45) – flesh-and-blood life as we know it, with the soul animating the body but in a perishable state. The sōma pneumatikon, by contrast, is the body as empowered by God’s Spirit (pneuma). Paul says “The first man Adam became a living being (soul); the last Adam became a life-giving Spirit” (15:45). Christ in his resurrection entered a new mode of existence in which, as the God-Man, He is filled with the Spirit and indeed pours out the Spirit. When we are raised “at His coming,” we too will have bodies completely enlivened by the Holy Spirit. We will be “spiritual” not by lacking a body, but by having a body fully infilled and directed by God’s Spirit, no longer merely by our natural psyche. We get a foretaste of this even now for Paul says believers already live partly in the “Spirit realm” (Romans 8:10–11), having the Spirit as a down payment; but in the resurrection, this will be consummated.

Crucially, psychikos and pneumatikos in Greek do not describe the material composition of the body (Paul does not say “it is sown a material body, raised an immaterial body”). They describe what orients the body; what “animating force” characterizes it. In 1 Corinthians 2:14–15, Paul uses the same words: “The natural person does not accept the things of the Spirit of God, for they are folly to him, and he is not able to understand them because they are spiritually discerned. The spiritual person judges all things, but is himself to be judged by no one.” Clearly, the psychikos person in that verse is not a disembodied soul; he’s an unregenerate man, lacking the Holy Spirit. And the pneumatikos person is not an angel or ghost; he’s a Spirit-filled believer, very much living a bodily life but governed by the Spirit of God. The adjectives describe orientation: one oriented to the merely human soul, the other oriented to the Spirit. Thus, when Paul says “it is sown a natural body, raised a spiritual body,” he is not denying the physical reality of the resurrection body. He is saying that today our bodily life is dominated by the “soul-ish” mode (and under sin, by the flesh), but in the resurrection our bodily life will be entirely dominated by the Holy Spirit – utterly holy, powerful, and immortal. The sōma pneumatikon will be a body totally governed by the Spirit, and perfectly suited for the realm of the Spirit (heaven/new creation). As A. Andrew Das succinctly puts it, “Even as the psychikos person of 1 Cor 2:14 has flesh and bones and is not just ‘soul’, the pneumatikos would have to be similarly endowed [with a real body of flesh and bones].”9 In other words, “spiritual” in biblical language does not mean “made of spirit” but “according to the Spirit.” A parallel expression is Paul calling the law “spiritual” in Romans 7:14. He certainly didn’t mean the law is non-physical or immaterial, but that it comes from God’s Spirit. Likewise, our spiritual body will be a true body (made tangible by God, as Jesus demonstrated when He invited Thomas to touch His post-resurrection wounds), but it will be entirely Spirit-empowered life. It will not be constrained by the vulnerabilities and lusts of “the flesh.” It will be sinless, deathless, glorious, and strong, but still recognizably human and physical, as was Christ’s when He ate broiled fish after rising (Luke 24:39–43).

DeMar and Burgess’s notion that “spiritual body” implies “not a physical body” has more in common with 19th-century liberal theology or ancient Gnosticism than with Paul. In fact, Ware documents that over the last 150 years, a number of critics tried to claim Paul believed in a non-fleshly resurrection, theorizing that the pneuma of the resurrection body was some kind of “astral” substance or ethereal light. But this Stoic-influenced reading has been thoroughly debunked. Ware notes, for example, that the Greek verb egeirō (“raise”) never means “assume into heaven as a spirit” – it always implies a raising up of what was down. And importantly, in Greek thought pneuma (spirit) was not typically used to speak of the heavenly realm’s substance (the ancients thought the stars were made of fire, not “spirit-air”). So Paul did not choose pneumatikon to denote some cosmic spirit-matter, but to make a theological point: the final stage of redemption is the Spirit completely vivifying the people of God. In context, Paul is correcting the Corinthians’ over-realized spirituality. Earlier he had to remind them that having the Spirit now is only a foretaste, and that we still await a resurrection. Some of them, thinking too “spiritually,” were denying the value or reality of bodily resurrection (hence “how foolish!” in v.36). Paul’s answer is not “we won’t have bodies,” but rather “the bodies we’ll have will be so Spirit-filled and glorious that all your carnal objections fall away.” Far from undermining the creedal affirmation of the body’s resurrection, the phrase “spiritual body” actually undergirds it: it tells us in what manner our very real bodies will live in the age to come; namely, in the realm of the Spirit’s power.

In sum, nothing in 1 Corinthians 15’s language implies an invisible or immaterial resurrection. Every term points to embodiment, transformed by God. Paul even says “the dead will be raised” (15:52) – using a verb (egeirō) that elsewhere in the chapter refers clearly to the raising of corpses (e.g. “Christ was raised on the third day” in v.4). The idea that resurrection occurs “when a believer dies and gets some kind of spiritual body in heaven,” as DeMar and Burgess teach, is found nowhere in the text, and is explicitly ruled out by Paul’s linking of our resurrection to “the last trumpet…at His coming” (15:23, 52). The faith of the church has always been that we look for the resurrection of the body still to come, when Christ returns; not that we consider it a past or purely individual phenomenon. Hebrews 11:39–40 says the faithful of past ages “did not receive what was promised… so that apart from us they should not be made perfect.” In other words, there is a corporate consummation awaiting, when all Christ’s people together will be raised and glorified. To claim it’s already behind us (or redefined as something else) is to “destroy the faith of some,” just as Paul warned.

Vos vs. Vos: Context Matters

Given how strongly the biblical evidence favors a transformed-yet-continuous resurrection body, it’s perplexing to hear Burgess enlist Geerhardus Vos on his side. Vos, a staunchly Reformed theologian, fully upheld the orthodox view of resurrection. Why the appeal to Vos, then? It appears Burgess lifted one technical observation from Vos – the allos/heteros distinction – and pressed it far beyond Vos’s intent. We have already seen what Vos actually concluded: the use of heteros in 1 Corinthians 15:40 underlines the major change in quality between our present earthly body and our future resurrection body; a change characterized by glory. Vos writes that each of the contrast-pairs in verses 42–44 (corruption vs. incorruption, dishonor vs. glory, weakness vs. power) flows from the fundamental contrast of psychical vs. pneumatic body. In other words, because the resurrection body is pneumatic (Spirit-transformed), it is incorruptible, glorious, and powerful; because our current body is psychical (soul-led and naturally perishable), it manifests corruption, dishonor, and weakness in this fallen world. Vos ponders how Adam’s body before the Fall could be called psychical and associated with those negative traits (since pre-Fall Adam wasn’t yet “dishonorable” or “corrupt” in the moral sense). He suggests that even the creational body, while not initially sinful, was naturally perishable; capable of corruption if not upheld by God, whereas the resurrection body will be by nature incapable of death or decay. This squares with the classic understanding that Adam’s continued life depended on God’s sustenance (e.g. the Tree of Life), whereas in glory our immortality will be permanently secured by the Spirit’s power. In any case, nothing in Vos’s discussion diminishes the continuity of identity or substance between the pre- and post-resurrection body. In fact, as quoted earlier, Vos explicitly rejects any notion that the introduction of the Spirit at resurrection “excludes the factor” of the original body. He even entertains and critiques a hypothetical “Spirit seed” idea some might use to explain continuity; only to conclude Paul doesn’t give a mechanism beyond affirming that the same thing sown is what rises by God’s power. Vos stands firmly with historic Christianity: resurrection is a supernatural transformation of the very person (body and soul) who died, not the creation of a different person or an unrelated body.

It’s worth noting that Vos wrote an entire Reformed Dogmatics earlier in his career, wherein he affirms that at the last day the bodies of the believers will be made like the glorious body of Christ (echoing Philippians 3:21) and that the selfsame bodies that have died shall be made alive. There is no hint of him deviating from the Westminster standards.

Question 9. What will be resurrected? In general we can answer: the same body that is laid in the grave. Thus there is identity. Scripture always speaks in such a way that this is presupposed. This corruptible must put on incorruption [1 Cor 15:53]. The resurrection of Christ is an example of the resurrection of believers. Now there can be no doubt whether the body of the Lord that rose was identical with that which was laid in the grave. It still even bore the signs of His suffering, the spear wound and the marks left by the hammered nails. The same thing is also implied in the image of sowing used by the apostle (1 Cor 15). What grows in the field is certainly not substantially the same as is placed in the furrow, but still it is also not something entirely new that is not connected with it.

The subject of the resurrection is the body, and that already entails that identity and continuity exist. Imagine that the soul received a new body. Could one then still say that the body rose? The soul would then be the subject of a transformation, not the body the subject of the resurrection. But Scripture speaks clearly of ἀνάστασις, ἐγείρεσθαι.10

Vos’s enduring contribution in biblical theology was to demonstrate the thoroughly eschatological nature of Paul’s thought; that through Christ’s resurrection, the powers of the age to come have already entered the present. Burgess, however, disparages systematic theology in favor of biblical theology, as if the two were rivals. Yet Vos himself held them together, recognizing that each safeguards the other from distortion.

By separating “the resurrection of the dead” from “the resurrection of the body,” Burgess loses Paul’s holistic vision of redemption. Systematic theology reminds us that salvation embraces the whole person. Christ redeems both soul and body (Romans 8:23). Biblical theology, for its part, reveals that this redemption consummates God’s original purpose in creation. Vos captured this unity when he wrote that “eschatology is teleology”—the doctrine of the end is the revelation of God’s goal for the created order. And that goal is not an ethereal heaven with disembodied spirits, but a resurrected humanity in a renewed cosmos, where the material creation is perfected and freed from decay (Romans 8:21). The podcast’s position, if taken to its logical end, sounds much like a form of neo-Gnosticism; treating the physical body as essentially disposable, something to be left behind for a “higher” spiritual mode. But Christianity from the beginning rejected that idea. The Apostles’ Creed insists on “the resurrection of the flesh (carnis),” and church fathers like Irenaeus and Tertullian wrote extensively against Gnostic teachers who denied the resurrection of our fleshly bodies. Ware’s research shows that all the orthodox early Christian writers interpreted 1 Corinthians 15 in line with a literal resurrection of the earthly body, made imperishable. It was only the heretical sects, who viewed matter as evil, that twisted “spiritual body” to exclude physicality. It is troubling that DeMar and Burgess are reviving an old heresy in new vocabulary.

Confessional Clarity: Why “Self-Same Body” Matters

The Westminster Confession of Faith (32.2) states: “At the last day, such as are found alive shall not die, but be changed: and all the dead shall be raised up with the self-same bodies, and none other, although with different qualities, which shall be united again to their souls for ever.” This single sentence holds together the very truths Paul holds together in 1 Corinthians 15; continuity (“self-same bodies, and none other”) and discontinuity (“different qualities”). Burgess caricatured this as “the body comes back just refurbished a bit”, but that’s a straw man. The confession nowhere says “just a little bit” of change. It leaves the extent of change open, only affirming that whatever comes is truly the same person/body that went down to the grave. How changed? “Different qualities” – and Scripture gives us those qualities in outline: imperishable, glorious, powerful, Spirit-driven, immortal. If one imagines the confession teaches a crude reanimation, e.g. a rotted corpse merely patched up, they are not reading the actual wording. When DeMar asks, “why is Paul spending so much time on this? When we’ve simplified it with a line in the confession, you’re going to get yourself self-same body back. Why do all of this for that? If that’s what this is all about,” the answer is: because Paul’s task was to convince skeptics and expound the glorious nature of that resurrection hope, something a creed only summarizes. The Westminster divines saw no contradiction between Paul’s detailed argument and their pithy statement; the latter is distilled from the former.

In fact, compare Westminster’s language to Paul’s in verse 53–54: “this mortal body must put on immortality.” Westminster says the self-same bodies will be raised “although with different qualities.” They are virtually identical affirmations. The mortal body (the one we have now) will put on the quality of immortality; thereby becoming “different” in quality (no longer mortal!). Paul’s phrase “put on” (endysasthai) implies enhancement or investiture, not replacement. It’s like a change of clothing; as 2 Corinthians 5:2 says, we long to be clothed with our heavenly dwelling, “so that what is mortal may be swallowed up by life” (not so that what is mortal may be discarded forever). The Westminster Confession echoes Job’s faith, “And after my skin has been thus destroyed, yet in my flesh I shall see God… My eyes shall behold, and not another” (Job 19:26–27, cited in WCF 32.2. The words “not another” could literally be rendered “not a stranger.” In other words, I will see God in a body that is truly mine, not an entirely different body belonging to someone else. God’s redemption does not scrap His handiwork; it heals and elevates it. That is why Christ’s own flesh saw no corruption (Acts 2:31) and was raised; to show that God’s solution to death is conquest of the grave, not an end-run around it. Our sin, not our bodies as such, is what God will eliminate. Our flesh, cleansed and glorified, is what God will restore.

The confessional phrase “self-same bodies” guards this truth. It preserves the personal identity and integrity of God’s creation in man. If resurrection meant God simply created new bodies for disembodied souls, death would actually have dominion over our old bodies; it would mean the old atoms and material are forever lost (and thus death “kept” them). But the gospel sting of resurrection is that death cannot even keep our dust! God snatches back even the bodies that death seemed to destroy, and makes them new. That’s total victory – “Death is swallowed up in victory” (1 Cor 15:54). By contrast, Burgess’s teaching implicitly surrenders our physical bodies to permanent death, replacing them with something else “heavenly.” This underestimates God’s power and overturns the biblical drama of redemption, which moves from creation (good), to fall (corruption), to redemption (restoration). Indeed, the goodness of the created body is vindicated when God raises it up and glorifies it, proving that nothing of His human image-bearers will be lost.

Given all this, we see that DeMar and Burgess have misconstrued both Paul and Vos. They turned heteros (different kind) into an argument for utter replacement, when really it’s about transformation of the same creature into a higher condition of existence. They turned “spiritual body” into a justification for an almost Docetic view of resurrection, whereas Paul meant it as the crowning description of our physical nature totally empowered by God’s Spirit. They pit “resurrection of the dead” against “resurrection of the body,” whereas in Scripture those are two sides of the same coin; to raise a dead person means to bring them up bodily from the grave (if you doubt it, just look at every instance of bodily resurrection in the Bible: e.g. Jesus raising Lazarus meant his corpse came out of the tomb refashioned to life). In asserting that “the person is raised but not the body,” Burgess has adopted a form of dualism foreign to the Hebrew worldview of the Bible. Biblically, a “person” is not whole unless body and soul are together. A “resurrection” that applied only to the soul (or to some other body) would not, in fact, be a resurrection of the person in the full sense. That’s why even in heaven right now, the departed saints – though with the Lord – are described as waiting for something. They are “spirits of the righteous made perfect” (Heb 12:23), and yet they still look forward to the “redemption of their bodies” (Rom 8:23). The intermediate state (soul in heaven pre-resurrection) is a temporary and incomplete state of blessedness. The final hope is embodied life on a New Earth. By teaching that believers receive their final form at death (with a “spiritual” body) and thus essentially skip the bodily resurrection, the DeMar/Burgess view collapses the intermediate and final state, and runs contrary to the clear future expectation taught by Paul and all Scripture.

Conclusion: Resurrection Glory – Continuity in New Creation

It is right to marvel at the “richness” of 1 Corinthians 15, as Burgess does. It is one of the most profound theological chapters in the Bible. But that richness is not found by rejecting the church’s historic understanding; it is found in expounding it; as Paul himself did, at length, to convince and thrill the doubters at Corinth. Rather than a “cheap proof-text” for an “open-and-shut” doctrine, Paul gives us a tapestry of resurrection theology: he ties together Christ’s victory, our union with Him, the conquest of death, the fulfillment of Israel’s hope (note his allusions to Isaiah and Hosea), and the breathtaking promise of complete transformation for those in Christ. The same bodies that bore the image of the dusty Adam will bear the image of the heavenly Christ (1 Cor 15:49). The same mortal frame that succumbed to disease and death will be clothed in immortality and glory. The continuity ensures that it is truly we who are redeemed; the discontinuity ensures that all the effects of sin and weakness are left behind. This is not only biblically accurate; it is pastorally precious. It means that in the resurrection, nothing good will be lost, only purified and elevated. We will recognize one another – as the disciples recognized the risen Jesus – and yet we will be more fully ourselves than ever.

By mischaracterizing the confessional view, DeMar and Burgess sadly set up a false dichotomy and then choose the wrong side. We do not have to choose between “resurrection of the dead” and “resurrection of the body.” It is both. The person who is raised is raised embodied; that’s exactly why Paul goes on about the nature of the body, to assure us that our future embodiment will be free from the limits of the old. We also need not choose between “continuity” and “discontinuity.” The New Testament teaches both continuity (it is truly Jesus risen; it is truly we who will rise) and discontinuity (a new, transformed mode of physicality, powered by the Spirit). Geerhardus Vos understood this well, as we’ve seen from his careful analysis. James P. Ware’s scholarship likewise reinforces that 1 Corinthians 15 stands in harmony with Luke 24, John 20, and the rest of apostolic witness: the resurrection of Christ and of His people is triumphantly physical; death and Hades give up their entire prey (Revelation 20:13), and the self-same bodies that were united to Christ in death will be united to our souls in resurrection life.

The Westminster divines chose the phrase “self-same bodies” not out of wooden literalism or lack of imagination, but to safeguard this glorious truth. Far from being “off the rails,” that phrase is a bulwark against the very error espoused on the podcast. It guards the church from the perennial Gnostic temptation to spurn God’s good creation. It reminds us that our God is the one who formed our bodies from the dust and breathed life into them, and He is not going to abandon the work of His hands. Redemption is re-creation, not abolition. In the resurrection, God will show forth the magnitude of Christ’s redemption, as every molecule once under the curse is transfigured into a mode of existence that can never die again. This is what Paul so eloquently sets forth in 1 Corinthians 15. The chapter is indeed “sublime”, and it fully supports the traditional creedal hope. Any teaching that says otherwise – that our resurrection is already past, or that it involves getting a different body than the one God fearfully and wonderfully made for us – is, to use Paul’s word, “foolish.” It is a misreading that impoverishes Christian hope and, inadvertently, aligns with those ancient voices that “denied the resurrection” to the alarm of the apostles.

In the end, we stand with Paul, with Vos, and with James P. Ware in affirming that the resurrection of the body is real. Our very bodies, united to Christ, will be raised and glorified by the power of the Spirit. This is “biblically and theologically accurate” – in fact, it is the only view that does justice to all the data of Scripture. The self-same Jesus who rose in glory will transform our lowly bodies to be like His glorious body (Philippians 3:20-21), and we will exult forever in the God who gives us the victory through our Lord Jesus Christ. “Therefore, my beloved brothers, be steadfast, immovable, always abounding in the work of the Lord, knowing that in the Lord your labor is not in vain” (1 Cor 15:58). That exhortation rests on the certainty of a future bodily resurrection. Any doctrine that undermines that certainty, however novel or sophisticated it sounds, should be firmly rejected. Let the historic Christian hope ring clear: Christ is risen, and because He lives, we shall live also; in our bodies made new, to the glory of God.

Geerhardus Vos, The Pauline Eschatology (Princeton, NJ: Geerhardus Vos, 1930), 80.

Ibid., 185.

A. Andrew Das, “Foreword,” in The Final Triumph of God: Jesus, the Eyewitnesses, and the Resurrection of the Body in 1 Corinthians 15 (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2025), ix.

Vos, Pauline Eschatology, 182.

Ibid., 181.

Ibid., 183.

Ware, Final Triumph of God, 377–379.

Vos, Pauline Eschatology, 185.

Ware, Final Triumph of God, 377–379; A. Andrew Das, “Foreword,” in Final Triumph of God, ix.

Geerhardus Vos, Reformed Dogmatics, ed. and trans. Richard B. Gaffin Jr., vol. 5 (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2012–2016), 272.

It is manifestly absurd to say "the human body is like a kernel of corn that dies and “is gone forever” so that a new plant can emerge." So, since the kernel of corn "is gone forever," from what does the new plant emerge? Nothing?

I’m a partial preterist. But I have to say I have yet to see any good answers to Gary’s questions. Im no theologian, so please forgive the ignorance of my questions.

The argument that Jesus resurrection is an example of ours seems wrong from the start.

There were resurrections before Jesus. The difference between Jesus and our resurrections is Jesus body “saw no decay”. Clearly we are not only seeing decay but in some cases such as fire we are all but annihilated. So if we are physically resurrected, it is very different from Jesus who saw no decay. So you have to wonder if that distinction ( he saw no decay) is for the very purpose of differentiating our resurrection from Jesus.

Here are more questions. Jesus still had his wounds. If I die because a shark took a chunk out of my leg do I come back with that chunk missing? If not then our resurrection is not like Jesus!

If a child dies in abortion, does he come back as a fetus? If not then our resurrection is not like Jesus!

If I die a shriveled old man do I come back a shriveled old man? If not then our resurrection is not like Jesus!

But the question I most want to answered is why is this belief so bad? Let me explain.

I think Dispensationalism where they essentially deny the kingdom is here, is much worse to the course of Christian history. But they are accepted as brothers. What is the damage caused by FP?

In a very basic way - the major issue with FP vs PP is meat suits or not? So what? Creators choice! Why do I care if I spend eternity in my meat suit or not?

Imagine this. You die and go to heaven. You’re with Jesus and you say, “Jesus, this is awesome! But man! I can’t wait to get my meat suit back! Then hanging with you will really be off the hook.”

Again, I’m a partial preterist trying to better understand. But I have to say the arguments against FP I am seeing remind me of the Pharisees who couldn’t give up the idea of a physical kingdom and trying to put their creeds above the law. Or modern dispys so desperate to hang onto the rapture and the idea of an earthly kingdom.

Of all my questions- why is the belief we don’t get our meat suit back so much worse than denying the kingdom is here now? Not saying it’s not. Just saying I don’t get why it is. Is our hope in spending eternity with God or in getting our meat suit back?

RE the creeds, I understand the historical weight they have. But it’s no different than the historical weight of the oral law. Someone argued they are different because the creeds are just recapitulation of the Bible not man made law! Cool, that means you don’t need them to make your argument since they are recapitulation, those arguments are already in the Bible. So to use the creeds is nothing more than to sub-textually argue that tradition is equal to Gods word.